I've recently become more interested in orchestral music (the vast majority of my classical music playlists consisted of piano music in the past), and especially starting to learn more about orchestral strings.

As a wind player myself, I don't have the best grasp of the possibilities with string instruments, but some recent listening has given me a better idea. From Finzi's fantastic Clarinet Concerto, Op.31 and Eclogue, Op.10 (which I hope to cover soon) to Jenkins's Concerto grosso 'Palladio', I'm learning a lot.

I'm writing today about Henryk Górecki's Three Pieces in Old Style for string orchestra. I first listened to this cycle of pieces on CD a few weeks back (same stacks/stash as before) and was really drawn by the first and third pieces.

Composed in 1963 at the request of Tadeusz Ochlewski, editor in chief of the music publisher PWM Edition, Three Pieces in Old Style is another composition, after Chorale in the Form of a Canon, in which Górecki draws on Polish early music. In that period, these compositions were a kind of sidetrack or marginal music for Górecki, and he did not give opus numbers to either of them.

[The] Three Pieces in Old Style are, indeed, worlds apart from his radically avant-garde work from the early 1960s. They are refined stylisations of Renaissance melodies, maintained in modal scales, with no traces of dodecaphony or aggressive sound and clear melodic lines and lively rhythms. ... [The] finale is both the culmination of the whole and the expressive peak of the cycle, coming after the first piece, a subtle, lyrical song with beautifully captivating sound, and the second, a folk dance based on a rhythmic ostinato.

Regardless of the composer’s intentions, Three Pieces in Old Style remains one of his most frequently performed works. The cycle also proved extremely important in the context of his later work and the role that quotations from early music came to play in his compositions from the late 1960s and early 1970s such as Old Polish Music and Symphony No. 2 “Copernican”. [1]

From the standpoint of a harmonic analysis, there aren't many substantive remarks I can make without making things unnecessarily complicated. Górecki makes ample use of successive suspensions, and in the third piece uses parallel cluster chords (which completely defies Roman numeral analysis; I'm not going to write a thirteenth chord).

Now that we have the context for the pieces and their inception, let's have a listen!

I really love the first piece of the cycle for its repetitive motif creating somewhat of a hemiola (superposition of two time signatures or pulses, in this case 6/4 on 3/2) and the use of natural minor chords.

First Piece, mm. 1-4

The rhythmic simplicity and visual simplicity of the opening figure on the score belies the harmonic density of what Górecki has written. I don't have a good idea of how I would notate these chords:

First Piece, mm. 1-4 (condensed)

These closed chords use the tension of minor and major seconds, even as long sustains, to support a repeating melody throughout the first piece.

First Piece, melodic ostinato

Górecki also places different numbers of instruments on each of the drones to change the function of the chords being played — that is, while all of the original chord tones are present, some carry more weight than others as a result of partitioned instrumentation (rather than actual dynamics). It's a subtle way to drive harmony without changing the hushed texture.

First Piece, episode "A" opening

First Piece, episode "A" opening (condensed to reflect relative weights)

Thus, we could actually start to write a harmonic analysis (though I won't attempt it here). As the piece progresses, note how the harmonic contour changes with these voicings. Stacked sustains (see below) also provide both harmonic direction and also a degree of ambiguity.

First Piece, stacked sustains in episode "B" opening

What I most love about the First Piece is the harmonic ambiguity between a minor and d minor because of Górecki's skillful use of the d Dorian mode (d minor with raised sixth #6 to B natural). Let's work with the first appearance of episode "B" -- at 0:56, we feel solidly in d minor, even though the bar prior feels like it has settled on a minor. At 1:04, it shifts again to a minor, helped along by the B natural in the first bar of episode "B" and the lowest pitch being A3. At 1:09, the use of E3 on beat 3 shifts the feel back to d minor, but the sustained G major at 1:11 sets us up for the a minor release in the next bar at 1:15. Thus, we can't really conclude that the piece is in either d minor or a minor -- it is simply in d Dorian: a prime example of how to write convincingly in a different mode.

Here's a brief listening guide / road map to the piece, with two distinct repeating episodes:

(0:00) Introduction with long tones lasts four bars, setting up motivic clustered chords.

(0:19) First instance of episode "A" with heavier C4-F4 voicing.

(0:56) First instance of episode "B" -- note the stacked sustains.

(1:15) Second instance of episode "A" with heavier C4-E4 voicing and accented suspensions in violas.

(1:53) Second instance of episode "B" -- note the divisi of first violins to include a higher voice.

(2:12) Third instance of episode "A" with the second split of the first violins playing the same motif twice here (different octaves each time).

(2:51) Third instance of episode "B" truncated to a four-bar phrase. For the first time, all the string enter on the same unison D4, and slowly break off into their own sustains throughout the descent. In the final bars, basses enter, rounding out the sound and providing a true sense of climactic energy as the unresolved G major blossoms.

The second piece, in C Mixolydian (B♭ accidental on C major), reminds me of a gavotte or bourrée some other dancelike piece, and it is reminiscent of an older style in spite of the the Mixolydian mode (major with flattened seventh). I also think I find this movement less captivating than the others because the repetition is so stark, in part due to the faster pace. For that reason, I'll leave you to listen to it. The major feature is this melodic ostinato.

Second Piece, melodic/harmonic ostinato

(3:17) First statement of opening melody and episode "A".

(3:42) Shift from 4/4 to 3/4 but retaining the motif signals episode "B". New harmony with D major and B♭ major also are introduced here.

(3:58) Interesting transition here keeps the harmonic motion in 3/4 but the time signature changes into 4/4, making...

(4:04) ...the reentry of episode "A" particularly unexpected.

(4:26) Episode "B" reentry.

(4:42) Similar harmonic transition as at 3:58 but with heavier articulations and dynamics.

(4:47) Blending of episode "A" contour and feel with episode "B" harmony with raised third of the supertonic (F#).

Someone in the comments of the video I've linked above suggests that the first and third pieces of the cycle are "proto-ambient" music, but I'm not sure I necessarily agree with that statement entirely.

While the third piece especially relies on drones (exactly what it sounds like, long sustains on unmoving notes), which are common in ambient music, I think it's more austere and purposeful (rather than atmospheric or ambient) in its simplicity, especially as Górecki specifies for all to play without vibrato with tutti senza vibrato. Even "minimalism" doesn't quite capture it; Górecki's phrases are drawn out, while minimalist music more frequently repeats shorter ideas.

Either way, whatever you'd like to call it, I really enjoy the beautiful dissonances and resolutions over the course of this piece. I also really like Górecki's use of the Dorian mode here as well (minor with raised sixth, so iv becomes IV in the mode), sitting on G major which feels like a dominant to C but subverting the cadence to d minor, suddenly but retroactively revealing the subdominant function of G major.

The constant shifting between the tonic centers of a and d does not feel jarring but rather transcendent, rising above musical boundaries of harmony within this diatonic language. In fact, the diatonic writing Górecki displays here makes these pieces of the titular "Old Style" — other pieces by Górecki, it turns out (I did not know this), rely on serialism, intense atonality and polytonality, and other hardcore 20th-Century composition techniques.

The drones on D2, E3, F4, G5, and A6 (visualized below so you can appreciate the wide range) serve as a translucent harmonic framework, setting the mode of d Dorian.

Drones of the Third Piece visualized in bass, treble, and alto clef

(It's insane regardless of what clef you look at it in)

Third Piece, episode "A" × 2

Another brief listening guide:

(5:30) Opening of Third Piece. First instance of episode "A".

(5:50) We're now finished with the first half of episode "A". This marks the first statement of the second five-bar phrase (2/2 × 2 + 3/2 × 3).

(6:15) Second instance of episode "A".

(6:39) Second instance of episode "A", second five-bar phrase. The E4—D4—|C4—D4—E4 motion in the first split of the second violins always gives me chills.

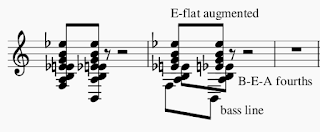

(7:11) First instance of episode "B": A traveling parallel cluster chord catches us (or perhaps just me) by surprise.

Third Piece, episode "B" opening

Here, we see the first traces of Górecki's fondness for serialism. This program note states it nicely:

It is only in the third piece that the expression of successive phrases in the old Polish song comes closer to that which we know from Górecki’s serial music. In this piece, the composer overlaps the string parts, starting the melodic line in each instrument with a different tone of the Dorian scale. This can recall for the audience Górecki’s serial speculations, and results in a dense, emotionally intensive eight-part harmonic structure. This finale is both the culmination of the whole and the expressive peak of the cycle. [1]

(7:51) Second statement of episode "B".

(8:41) After a startling silence, episode "A" returns. The absence of the drone gives this restatement a grounding and firm sense of resolution.

(9:10) Episode "B" cluster chords return.

(9:33) The rearticulation of the cluster chord and its seamless melting into G major gives me goosebumps.

(9:44) Resolute crescendo to the closing on d minor.

I hope you enjoyed this cycle of string orchestral pieces as much as I did. Share this post if you did and leave your thoughts below!

[1] Three Composers / Ninateka. Three Pieces in Old Style. Accessed in English at <https://ninateka.pl/kolekcje/en/three-composers/gorecki/audio/trzy-utwory-w-dawnym-stylu-na-orkiestre-smyczkowa>.