Silvestre Revueltas (1899-1940) was a Mexican composer and violinist, whose artistic motivations propelled him into revolutionary musical undertakings. Sensemayá (1937) may be his best-known work, though I only listened to it for the first time this past Thursday while working through a massive collection of classical music CDs I was given. I had first heard of the piece in a TwoSet Violin video (Sightreading Devillish [sic] Time Signatures); that was my only exposure until recently.

Historical Context

Historical Context

Revueltas was first influenced to write Sensemayá after listening to a recitation of a poem of the same name by Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén. Guillén and Revueltas became close friends through La Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (LEAR) (League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists) in Mexico in the late 1930s. They not only shared political opinions and a passion for activism, but also were closely allied as artists — Guillén the poet and Revueltas the composer [1].

Their friendship was galvanized after the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936. Revueltas was the president of LEAR at the time and helped LEAR organize the 1937 Congreso de (Congress of) Guadalajara, which Guillén attended after his first invitation to LEAR earlier that year. Ultimately, because of their shared philosophies on art and interest in each others' work, they began "cross-fertilizing" each other's work and breaking down the insularity of letters and music [1].

(I won't go into more detail on the relationship between Revueltas and Guillén, but this amazingly detailed article in Ethnomusicology Review takes a deep dive.)

The poem written by Guillén is inspired by an Afro-Cuban chant for a sacrificial snake, which he used as the subtitle ("canto para matar una culebra" or "chant to kill a snake"). "The word sensemayá is a combination of sensa (Providence) and Yemaya (Afro-Cuban Goddess of the Seas and Queen Mother of Earth). The poem poeticizes an Afro-Caribbean snake dance rite conducted by the practitioners of the Palo Monte Mayombe religion." [1].

Since I do not know Spanish, I decided to read a transcription and translation of the poem [4]. The combined images I visualize from the works by Guillén and Revueltas are both terrifying and enticing at once. The images of metaphoric glass eyes ('con sus ojos de vidrio') and a snake slithering through the grass unseen ('caminando se esconde en la yerba') is powerful. I feel that I can better appreciate the cultural significance of the text — because of its connection to the Palo Monte Mayombe religion — after reading the translation.

Sensemayá — The Orchestral Work

Now that we have the context laid down, let's have a listen and follow along! I like one particular recording [5] by Eduardo Mata with the New Philarmonia Orchestra best, but I've also linked to the 2012 Ukrainian premiere [6] by Hobart Earle with the Odessa Philharmonic Orchestra and the 1962 American performance by Leonard Bernstein with the New York Philharmonic [7]. All of the links in the text are to the Mata recording, my personal favorite, though the Bernstein recording is a classic!

(0:05) Revueltas depicts the eponymous snake through winding contours of woodwinds slurs, especially ominous as it first emanates from a single bass clarinet. Revueltas's choice use of both standard percussion (xylophone, cymbals, tom-toms, glockenspiel, celesta, gongs, bass drum, and piano) and cultural Mexican/Latin percussion instruments (claves, raspador, maracas, small "Indian" drum, and gourd) is established in the opening of the piece as well [8]. Originally, the piece was scored for a small chamber orchestra, but it was reworked for a larger orchestra in 1938.

The piece also opens with the accents-only part of the rhythm I described earlier. In this case, the 'rest' in the line of the poem is emphasized with a note in its place. This forms the first percussion ostinato (P).

(0:14) Revueltas starts with a really sparse texture and slowly stacks up juxtaposed musical elements. On top of W and P, he sets up the ostinato bass line (B):

The ostinato bass line addition is joined by accents on beat 7 of each bar with the claves, further reinforcing P. The placement of an accented percussion attack in the 'rest' of the "¡Mayombe-bombe-mayombé!" rhythm emphasizes it, solidifying the 7/8 pulse (4+3/8).

(0:23) The first melodic strain (M1) comes from tuba solo — I wouldn't be surprised if this is a common excerpt for tuba players auditioning for orchestras. Revueltas marks dynamics in the solo very specifically to emphasize dissonant peaks. The phrase lasts twelve bars, and can be felt in three four-bar chunks (implied by the rehearsal numbers).

(0:44) A single muted horn makes a dissonant call (H1), signaling a repeat of the first melody (M1) in the tuba, joined by muted trumpet solo and English horn to sharpen the texture.

(1:38 again) From the highlighted score, you can see that Revueltas throws each successive new idea with a slight delay. First we hear S repeated three times, H1, an exchange between T1 and S, the strings picking up P, T1 again, and the staggered entrances of H2 and T2.

More melodic fragments are scattered throughout the woodwinds and brass over the next short section, closing with a triplicate repetition of S (2:21) before the next episode begins.

(2:29) Dropping to a lighter instrumentation again, Revueltas uses the softer dynamics to emphasize the gritty and aggressive trombone line (T3) that stings the listener. This motif resemble yet another verse of Sensemayá, progressing along in the poem. Although Revueltas continues to weave musical ideas that are not related to or derived from the recitation, like the new melody (M2) played by trumpet solo, he works them together compellingly.

(2:43) As the section progresses, high woodwinds (flute solo and E♭ clarinet) are added to M2, violas and cellos enter on S pizzicato (plucking the strings), and horns enter on S legato (slurred or connected):

This massive first climax roughly marks the halfway point.

(3:39) After reducing to minimal percussion and transferring T1 to a small "Indian" drum (along with the full P pattern on tom-toms and the partial on claves), Revueltas slowly writes earlier motifs into the music.

(4:02) These ideas are slowly expanded, bar by bar, until the time signature is literally alternating between 7/8 and 7/16. In doing so, both old ideas (P, T1, W, and B) and new ideas (H3 and 7/16) meet in the middle. Revueltas also introduces a string flourish (F) that makes only two appearances.

(4:15) Revueltas then weaves the second melody (M2) into the ever-changing time signature, all over the alternation between the old rhythmic motifs (P, T1, W, and B) and the new 7/16 motif.

[1] Zambrano, Helga (2014). Reimagining the Poetic and Musical Translation of “Sensemayá”. Ethnomusicology Review, UCLA.

[2] Sykes, Kathleen (2019). "The Musical Poetry of Sensemayá". Utah Symphony Orchestra.

[3] Guillén, Nicolás (1958). Recording of "Sensemayá" radio recitation via YouTube. Uploaded by Riva, Manuel Rodríguez (2013).

[4] Guillén, Nicolás (1934). "Sensemayá" (West Indies, Ltd.). Translation by Jones, William Knapp. University of Pennsylvania.

[5] New Philharmonia Orchestra, dir. Mata, Eduardo, Sensemayá (Revueltas, 1938).

[6] Odessa Philharmonic Orchestra, dir. Hobart Earle (2012), Sensemayá (Revueltas, 1938).

[7] New York Philharmonic, dir. Leonard Bernstein (1962), Sensemayá (Revueltas, 1938).

[8] Schwarm, Betsy. "Sensemayá: work by Revueltas". Encyclopedia Britannica.

[9] Reco-reco - Wikipedia (2019).

All score and part excerpts taken from the 1949 G. Schirmer Edition (New York) via IMSLP.org.

Their friendship was galvanized after the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936. Revueltas was the president of LEAR at the time and helped LEAR organize the 1937 Congreso de (Congress of) Guadalajara, which Guillén attended after his first invitation to LEAR earlier that year. Ultimately, because of their shared philosophies on art and interest in each others' work, they began "cross-fertilizing" each other's work and breaking down the insularity of letters and music [1].

(I won't go into more detail on the relationship between Revueltas and Guillén, but this amazingly detailed article in Ethnomusicology Review takes a deep dive.)

Sensemayá — The Poem

The poem written by Guillén is inspired by an Afro-Cuban chant for a sacrificial snake, which he used as the subtitle ("canto para matar una culebra" or "chant to kill a snake"). "The word sensemayá is a combination of sensa (Providence) and Yemaya (Afro-Cuban Goddess of the Seas and Queen Mother of Earth). The poem poeticizes an Afro-Caribbean snake dance rite conducted by the practitioners of the Palo Monte Mayombe religion." [1].

The religion operates in concordance with nature, and it places strong emphasis on the individual’s relationship to ancestral and nature spirits and its practitioners. The Palo mayombero specialize in infusing natural objects with spiritual entities to aid or empower humans to negotiate the problems and challenges of life. ... In the poem, the snake is portrayed not only as the snake on earth to be killed, but as the sacred Infinite represented by the Snake itself — a spiritual entity with which the mayombero or Palo infuses the snake. The killing of the snake, a sacred creature, symbolizes renewal, fertility, growth, and wisdom. This is because snakes shed their skin annually, linking them to the rainbow, heavens, gods, and the earth for African and pre-Christian civilizations.The poem was meant to be listened to rather than read on paper [2], and this is really clear from the cadence, pace, and rhythm of Guillén's recitation, which I highly encourage you to listen to here [3]. Revueltas might have heard a rhythm like the one below in Guillén's recitation, thus deciding to use a lopsided 7/8 time signature as the foundation of the piece.

Since I do not know Spanish, I decided to read a transcription and translation of the poem [4]. The combined images I visualize from the works by Guillén and Revueltas are both terrifying and enticing at once. The images of metaphoric glass eyes ('con sus ojos de vidrio') and a snake slithering through the grass unseen ('caminando se esconde en la yerba') is powerful. I feel that I can better appreciate the cultural significance of the text — because of its connection to the Palo Monte Mayombe religion — after reading the translation.

Sensemayá — The Orchestral Work

(0:05) Revueltas depicts the eponymous snake through winding contours of woodwinds slurs, especially ominous as it first emanates from a single bass clarinet. Revueltas's choice use of both standard percussion (xylophone, cymbals, tom-toms, glockenspiel, celesta, gongs, bass drum, and piano) and cultural Mexican/Latin percussion instruments (claves, raspador, maracas, small "Indian" drum, and gourd) is established in the opening of the piece as well [8]. Originally, the piece was scored for a small chamber orchestra, but it was reworked for a larger orchestra in 1938.

Opening, with woodwind sixteenth notes (W) and first percussion ostinato (P)

The piece also opens with the accents-only part of the rhythm I described earlier. In this case, the 'rest' in the line of the poem is emphasized with a note in its place. This forms the first percussion ostinato (P).

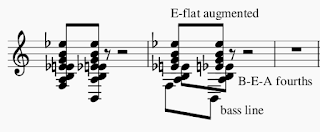

(0:14) Revueltas starts with a really sparse texture and slowly stacks up juxtaposed musical elements. On top of W and P, he sets up the ostinato bass line (B):

Ostinato bass line in bassoon (B)

Entrances of bassoon on B and

claves with accented beat 7 of P

The ostinato bass line addition is joined by accents on beat 7 of each bar with the claves, further reinforcing P. The placement of an accented percussion attack in the 'rest' of the "¡Mayombe-bombe-mayombé!" rhythm emphasizes it, solidifying the 7/8 pulse (4+3/8).

(0:23) The first melodic strain (M1) comes from tuba solo — I wouldn't be surprised if this is a common excerpt for tuba players auditioning for orchestras. Revueltas marks dynamics in the solo very specifically to emphasize dissonant peaks. The phrase lasts twelve bars, and can be felt in three four-bar chunks (implied by the rehearsal numbers).

First melody in tuba (M1)

Entrance of tuba on M1 and addition of double bass to B

(0:44) A single muted horn makes a dissonant call (H1), signaling a repeat of the first melody (M1) in the tuba, joined by muted trumpet solo and English horn to sharpen the texture.

First horn call (H1)

H1 signals repeat of M1

(0:48) Here, the melody starts a bar late and takes eleven bars to complete instead of twelve as before. It also swaps segments of the initial statement of M1, which changes the groupings (no longer in groups of four).

(1:13) Revueltas repeats M1 for a third time in the introduction with more (and varied) instrumentation. He replaces the bass drum with the raspador on P, a scraped percussion instrument related to the more familiar instrument in Latin music, the güiro [9]. He also doubles the clarinets and adds first flute to W; adds first oboe, first piccolo (besides Sousa's "The Stars and Stripes Forever," I don't know of another piece that calls for more than one piccolo), and E♭ clarinet to M1; doubles bassoons and increases the dynamic on basses for B; and adds muted trombones on P, further sharpening the texture.

So far, I've left out ideas that were introduced earlier, but let's take a look before and after rehearsal number 8 with all motifs shown:

So far, I've left out ideas that were introduced earlier, but let's take a look before and after rehearsal number 8 with all motifs shown:

Third repetition of M1 with bolstered instrumentation

(1:38) The melody fades into nothingness and a new episode begins. A new motif takes center stage, marking the first appearance of all the strings (except basses). A new string ostinato pattern (S) also seems to reflect the cadence of the poem's opening:

You can hear that a lot changes here. In addition to H1 becoming a main melodic feature in this fragmented section, S enters as a melody, more woodwinds have sixteenth notes (W), and P is transfused into the violin and viola parts.

We also see the addition of new trombone patterns. The first (T1) is a recurring rhythm in both brass and percussion, while the second (T2) happens only in trombones (although related fragments do show up in other instruments). A new horn call (H2) is also added, during which T2 appears.

String ostinato pattern (S)

You can hear that a lot changes here. In addition to H1 becoming a main melodic feature in this fragmented section, S enters as a melody, more woodwinds have sixteenth notes (W), and P is transfused into the violin and viola parts.

We also see the addition of new trombone patterns. The first (T1) is a recurring rhythm in both brass and percussion, while the second (T2) happens only in trombones (although related fragments do show up in other instruments). A new horn call (H2) is also added, during which T2 appears.

Entrances of S, continued H1, exchanging instrumentation on P,

and new patterns T1, T2, and H2

(1:38 again) From the highlighted score, you can see that Revueltas throws each successive new idea with a slight delay. First we hear S repeated three times, H1, an exchange between T1 and S, the strings picking up P, T1 again, and the staggered entrances of H2 and T2.

More melodic fragments are scattered throughout the woodwinds and brass over the next short section, closing with a triplicate repetition of S (2:21) before the next episode begins.

(2:29) Dropping to a lighter instrumentation again, Revueltas uses the softer dynamics to emphasize the gritty and aggressive trombone line (T3) that stings the listener. This motif resemble yet another verse of Sensemayá, progressing along in the poem. Although Revueltas continues to weave musical ideas that are not related to or derived from the recitation, like the new melody (M2) played by trumpet solo, he works them together compellingly.

Aggressive trombone line (T3)

New melody (M2) played by trumpet solo

Entrances of T3 and M2

(2:43) As the section progresses, high woodwinds (flute solo and E♭ clarinet) are added to M2, violas and cellos enter on S pizzicato (plucking the strings), and horns enter on S legato (slurred or connected):

Viola and horn on modified S figure

More instruments on M2 and entrance of violas/cellos/horn on S

(3:10) After a series of extremely dissonant chords (note the piano entrance)...

...(3:18) Revueltas changes the time signature for the first time (9/8 = 3/4 + 3/8), drops the ostinato bass line, and adds yet another rhythm from the Sensemayá recitation, occurring seven times in a row(!). The sensemayá triplet motif makes its first appearance here. (There is also a clave in the full score excerpt.) Though the lyrics do not exactly match the text that Guillén wrote in terms of syllable stress, the relationship is clear:

...(3:18) Revueltas changes the time signature for the first time (9/8 = 3/4 + 3/8), drops the ostinato bass line, and adds yet another rhythm from the Sensemayá recitation, occurring seven times in a row(!). The sensemayá triplet motif makes its first appearance here. (There is also a clave in the full score excerpt.) Though the lyrics do not exactly match the text that Guillén wrote in terms of syllable stress, the relationship is clear:

Modified T3 and the sensemayá motif with lyrics

Modified T3 and sensemayá motifs in full score

This massive first climax roughly marks the halfway point.

(3:39) After reducing to minimal percussion and transferring T1 to a small "Indian" drum (along with the full P pattern on tom-toms and the partial on claves), Revueltas slowly writes earlier motifs into the music.

Halfway point similar to opening, building up the texture

(3:52) He then begins to work a 7/16 time signature into the 7/8 feel, suddenly interrupting the original texture with dry double reed (oboes, English horn, and bassoons) staccato pecking (7/16). He also brings T1 back to the brass (trumpets) and a new horn call motif (H3).

First bar of 7/16 (7/16 motif) and following bars

(4:02) These ideas are slowly expanded, bar by bar, until the time signature is literally alternating between 7/8 and 7/16. In doing so, both old ideas (P, T1, W, and B) and new ideas (H3 and 7/16) meet in the middle. Revueltas also introduces a string flourish (F) that makes only two appearances.

Mixing of old (P, T1, W, and B) and new (H3, 7/16, and F1) ideas

(4:15) Revueltas then weaves the second melody (M2) into the ever-changing time signature, all over the alternation between the old rhythmic motifs (P, T1, W, and B) and the new 7/16 motif.

M2 over constant alternation between 7/8 and 7/16

(4:38) Revueltas brings in one more new trombone idea (T4, which actually shows up in oboes, English horn, and both piccolos) before the second climax of the piece. This one has an identical pattern to the "la culebra muerta" verses of original poem. Its two occurrences allow for the exact mapping of both rhythmically identical verses.

Now that we have collected all the main trombone ideas, we can see that the entire poem is encoded in these musical fragments:

(4:54) The second climax brings the strangest rhythmic anomaly of all. As if the time signatures constantly switching didn't flip you on your head already, Revueltas writes an absurd 5½/8 time signature!

Conductor Hobart Earle points out that Revueltas could have written it as 11/16 ... so, why 5½/8? Revueltas has, looking at it one way, appended a 7/16 bar to a bar of 2/8. Rather than marking it in 11/16, which obfuscates the pulse of these three bars, Revueltas offers the performer a suggestion to feel the bar as 5½/8 = 2/8 + 3½/8 (where 3½/8 is the same as 7/16).

In addition to the rhythmic complexity, the chords (in red) preceding the 7/16 motifs are quite dissonant as well. Accounting for the transposition of each of the instruments involved, here is what that chord looks like:

(4:59) This leads into a four-times repeated discordant chaos of glissandi and another exchange between a different version of T3 and the sensemayá motif. Alternating high and low sforzando chords sit between the melodic glissandi and bass notes between other glissandi.

(5:10) After this suspenseful climax, Revueltas writes a four-bar transition into the final melodic gesture. Combining all of the first rhythmic motifs (P, T3, W, and B), Revueltas writes a huge molto crescendo, dynamically broadening into the coda. Note the return of the "¡Mayombe-bombe-mayombé!" rhythm in the trumpets, which also reappears in the final stanza of the original poem.

(5:19) This grandiose climax superimposes both melodies M1 and M2 and "¡Mayombe-bombe-mayombé!" S over the original rhythmic backdrop (P, T1, W, and B). See if you can find both M1 and M2 in the score.

(5:32) The discordance keeps growing throughout the next several bars, with so much rhythmic activity that the beat becomes difficult to find. Without any motivic coloring, here is what the score looks like:

(5:50) The piece returns with the string flourish (F) and horn call (H3) from earlier before a series of brass punches over B.

(5:56) With a final flashing sensemayá motif, the piece comes to a close.

I hope you enjoyed this detailed analysis of Sensemayá! Share this post if you enjoyed it and leave your comments below!

New trombone idea (T4), also appearing in other instruments

Transition into the second climax with T4

Now that we have collected all the main trombone ideas, we can see that the entire poem is encoded in these musical fragments:

Sensemayá: the poem embedded in the composition

(4:54) The second climax brings the strangest rhythmic anomaly of all. As if the time signatures constantly switching didn't flip you on your head already, Revueltas writes an absurd 5½/8 time signature!

Beginning of second climax, in 5½/8

Conductor Hobart Earle points out that Revueltas could have written it as 11/16 ... so, why 5½/8? Revueltas has, looking at it one way, appended a 7/16 bar to a bar of 2/8. Rather than marking it in 11/16, which obfuscates the pulse of these three bars, Revueltas offers the performer a suggestion to feel the bar as 5½/8 = 2/8 + 3½/8 (where 3½/8 is the same as 7/16).

In addition to the rhythmic complexity, the chords (in red) preceding the 7/16 motifs are quite dissonant as well. Accounting for the transposition of each of the instruments involved, here is what that chord looks like:

Accented dissonant chords of second climax

(4:59) This leads into a four-times repeated discordant chaos of glissandi and another exchange between a different version of T3 and the sensemayá motif. Alternating high and low sforzando chords sit between the melodic glissandi and bass notes between other glissandi.

Continuation of second climax, with break

(5:10) After this suspenseful climax, Revueltas writes a four-bar transition into the final melodic gesture. Combining all of the first rhythmic motifs (P, T3, W, and B), Revueltas writes a huge molto crescendo, dynamically broadening into the coda. Note the return of the "¡Mayombe-bombe-mayombé!" rhythm in the trumpets, which also reappears in the final stanza of the original poem.

Transition into final climax (heavy vertical line)

(5:19) This grandiose climax superimposes both melodies M1 and M2 and "¡Mayombe-bombe-mayombé!" S over the original rhythmic backdrop (P, T1, W, and B). See if you can find both M1 and M2 in the score.

Final melodic gesture

(5:32) The discordance keeps growing throughout the next several bars, with so much rhythmic activity that the beat becomes difficult to find. Without any motivic coloring, here is what the score looks like:

(5:50) The piece returns with the string flourish (F) and horn call (H3) from earlier before a series of brass punches over B.

Closing of Sensemayá

(5:56) With a final flashing sensemayá motif, the piece comes to a close.

I hope you enjoyed this detailed analysis of Sensemayá! Share this post if you enjoyed it and leave your comments below!

[2] Sykes, Kathleen (2019). "The Musical Poetry of Sensemayá". Utah Symphony Orchestra.

[3] Guillén, Nicolás (1958). Recording of "Sensemayá" radio recitation via YouTube. Uploaded by Riva, Manuel Rodríguez (2013).

[4] Guillén, Nicolás (1934). "Sensemayá" (West Indies, Ltd.). Translation by Jones, William Knapp. University of Pennsylvania.

[5] New Philharmonia Orchestra, dir. Mata, Eduardo, Sensemayá (Revueltas, 1938).

[6] Odessa Philharmonic Orchestra, dir. Hobart Earle (2012), Sensemayá (Revueltas, 1938).

[7] New York Philharmonic, dir. Leonard Bernstein (1962), Sensemayá (Revueltas, 1938).

[8] Schwarm, Betsy. "Sensemayá: work by Revueltas". Encyclopedia Britannica.

[9] Reco-reco - Wikipedia (2019).

All score and part excerpts taken from the 1949 G. Schirmer Edition (New York) via IMSLP.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment